May was a delightfully busy month, book-wise! June.....was certainly a month! Managed to finish 3 :)

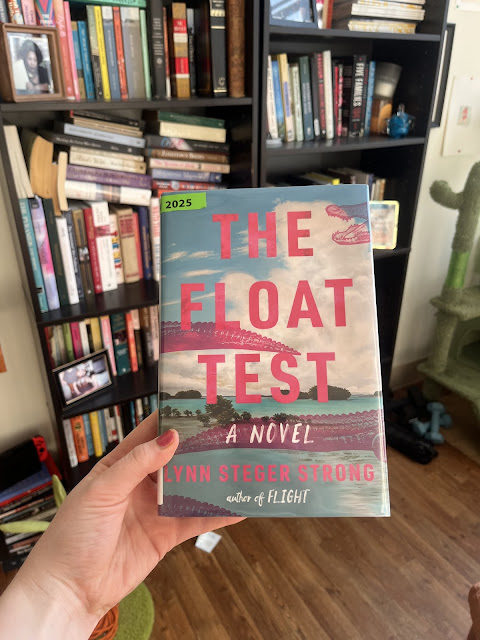

A(n insufferable) family saga

I had high hopes for this book. Lynn Steger Strong wrote a beautiful article in April for The Atlantic titled "Joan Didion's Books Should Have Been Enough" that I completely agreed with. Her article was a breath of fresh air amidst the countless other takes I saw delighting in the publication of an incredibly private person's therapy notes. Alas, Lynn's writing prowess & correct Didion opinions were not enough to save this book.

Generally, books that explore the highly dysfunctional inner workings of a family unit are right up my alley (see: Long Island Compromise by Taffy Brodesser-Akner). As a rule, the characters that populate dysfunctional stories are selfish, neurotic, controlling, or just plain bananas. But unlike the characters of Taffy's novel, for example, Lynn's characters are broken, selfish, lost...and stay that way. There is 0 character development for them. The novel is filled with insufferable people who act horribly and.....that's it. I kept waiting for even a glimpse at resolution—even if it didn't happen on the pages themselves, surely she'll give us a hint that things get better once the novel ends!? It never came.

The perspective of this novel is very...unique. Our narrator is Jude (aka Judith), sister to Jenn, Fred (aka Winnifred), and George (the sole brother). Somehow, via Jude's narrative, we are allowed access to Fred and George's inner selves, but not to Jenn nor even to Fred herself? So maybe we're only accessing Jude's projected understanding of her siblings? Maybe....but that's never made clear. I understand—adore, even!—an unreliable narrator, but the arc of discovery of Jude's unreliability is wholly missing. Jude and Fred are quietly feuding the whole novel (I shan't spoil any details) and that just sort of fizzles out by the end without satisfaction for anyone involved.

There is 0 examination of why Jude and Fred chose traditionally boy nicknames for themselves, or why they both follow the same career & life trajectory but somehow maintain a living grudge. The father of this crumbling mess of a family is a random character that floats in and out of scenes and is, functionally, a set piece. He had much more potential than we ever were afforded the opportunity to enjoy.

An enthralling multigenerational octopus

I love a story that's crafted by the intricate weaving together of (seemingly) distinct pieces and Madeleine proves herself an absolute master at that with this novel. We follow three generations of family through the roiling change of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, culminating in the frantic energy of Tiananmen Square.

One of the major plot lines of Madeleine's novel follows Wen the Dreamer and his wife, Swirl, in their quest to finish a never-ending love story written by an anonymous author with chapters scattered across China. As the two become victims of Mao Zedong's land reform movement, they begin writing their own installments of the story to hide in plain sight and encourage the rebels. By the end, it's impossible to tell where The Book of Records leaves off and Madeleine's novel begins, a device that reminds me a great deal of Italo Calvino's Se una notte d'inverno, un viaggiatore—one of my favorite experimental lit tales. I spent one full day enthralled in this story, and I was honestly sad to get to the end! I felt so endeared to each of the characters by the end.

A peek behind the Great Firewall

Even in today's hyper-connected world, the daily workings of Chinese society remain shrouded in mystery—no small feat, considering China is one of the most populated and powerful nations on Earth. Emily Feng is a brave journalist that dares to expose the chokehold the ruling Chinese Communist Party (tries to) hold on its people. Emily traverses a lot of ground—literally. She explores far-flung corners of China and the Chinese diaspora, interviewing Uyghur families, human rights lawyers in hiding, and exiles living in Hong Kong, Canada, and Taiwan.

This is a heavy read to get through, lengthy in both page count and topic. Emily is nearly absent from her pages—not entirely surprising in a nonfiction book, but her absence is notable for a topic that is so dear to her, personally.

Pregnancy hormones meet the algorithm

As a scholar of contemporaneity and digitality, I love reading works that delve into any digital niches. Which is how I stumbled into this book about the intersection of cyberspace and pregnancy & parenthood. Amanda writes about period and pregnancy-tracking apps, mommy influencers, nursery robots, targeted ads, and—her strongest passages, in my opinion—she writes movingly about the experience of her child's diagnosis with a rare genetic abnormality.

As a scholar of contemporaneity and digitality, and an Aquarius (which I find probably the more likely culprit), I find myself existing in a highly reactive headspace when reading about other people's Internet use habits. Amanda describes her fixation with pregnancy and parenthood Reddit threads, message boards, and apps and the incredibly negative impact it has on her mental health. At a certain point...I couldn't help but think, "well...stop looking? Log off?" I realize this is a reaction without nuance, but I ran into that thought over and over again while reading that it became a frequent refrain.

A memoir (Chat-GPT's version)

If I have talked to you about books at all in the past 2 years, it's a good bet that my love for The Immortal King Rao came up. I adored Vauhini's debut novel, so I was extremely excited for the release of her latest book. Well, they say hope springs eternal....

My feelings about AI are incredibly large. I studied it while earning my MA and my thesis dealt in large part with trans- and posthuman technology, which includes machine learning and AI. So I recognize that this may disqualify me from participation in the general populace of people who pick up a common interest book like this one. I wanted to learn something new here, but my first thought at the end of this book was, "That's it?" There was nothing....revolutionary about this text. Vauhini included various interactions she had with chat bots, but I have no idea for what purpose. My eyes started glazing over at the repetition of AI's chapter-end summaries. I'm not sure what we were meant to get from those inclusions...

Much like my complicated feelings about Eula Biss' Having and Being Had, there are multiple elements of the memoir portion, in particular, that delve into Amazon and various other intrusions of tech oligarchy into our daily lives that feel overly casual to the point of complacency. Vauhini writes about an argument she had with a friend who doesn't use Amazon, on principle. Vauhini responds, "Well, one person not using it doesn't really make a difference, does it?" To her credit, Vauhini recognizes the mistread in her response and reaches back out to the friend. But then...she spends the rest of the chapter defending why she still uses Amazon? Her decision is to force herself to review everything she buys on Amazon as a kind of "punishment"? Except, as a tech journalist and author, Vauhini knows that any interaction with the algorithm fuels it further, so...? I really wanted to like this book and I'm bummed I walked away so disappointed.

If an algorithm was also a city

Have you ever asked yourself, "What if a generative AI model became a physical being, and also the living structure of a town? And also, what if said AI-fueled society was on the verge of class warfare?" Apparently, Erika Swyler has, and this novel is her answer. Obviously, I am passionate about the subject matter, which I'm sure has monumentally biased my opinion....because I really like this book, which means forgiving it for issues I would not forgive in other books.

Much in the same way as successful fantasy authors, Erika manages to build a whole world with entirely new rules, social order, beliefs, and language. Unlike most fantasy novels (looking at you, Priory of the Orange Tree), Erika's novel accomplishes this without being the size of a cinderblock. Instead of magic, the society Erika creates runs on technology. Erika's novel is supremely successful at investigating the posthuman tensions that accompany the—for lack of a better term—"birth" of an AI system into a physical form.

I think the plot as a whole tries to bite off more than it can chew. We get a lot of insight into one particular class of characters—the Sainted—and very little insight into the others. So when it comes time for brewing tensions to escalate into a full-on class war, it feels really underbaked. I wish we got more insight into the motivations for the non-Sainted characters, too. (If you're interested in reading a much more well-rounded take than my brief one, William Emmons' reviewed Erika's book for the Ancillary Review and I really enjoy their thoughts.)

A field manual for resilience

In the mornings—on the good ones, anyway—I make a cup of tea, roll out my yoga mat, and pick up a book. In May, that book was Kaira Jewel Lingo's We Were Made For These Times. This book is a balm in every sense of the word. The past few months have been full of tremendous change for me and Kaira's beautiful, thoughtful writing was a calming reminder of how adept our bodies & souls are for handling moments of transition.

Kaira's writing includes personal reflections, anecdotes, journal prompts and guided meditations. I first encountered Kaira on an episode of the 10% Happier podcast. A former Buddhist nun, Kaira is now a layperson with an inspiring practice and the ability to transmit her calm energy to you, even over the page.

Man vs. bear

Back on my animal fiction game! (I need a better name for that genre...happily accepting suggestions.) This book had a similar vibe to the The Overnight Guest by Heather Gudenkauf in that the setting was as influential and present as a character. Eowyn takes us to rural Alaska in this novel, where we meet Birdie—a flighty single mother struggling to get it together, her young daughter, Emaleen, and Arthur—the town outcast. Birdie decides to move with Emaleen to Arthur's remote cabin deep in the Alaskan woods, much to the chagrin of Birdie's friends in town and Arthur's recluse father.

At its core, this novel is really about wanting. Birdie wants freedom. Emaleen wants stability. And Arthur wants more than anything to take care of Birdie & Emaleen, to prove that he can love them enough to save them from himself. This story is a refreshed version of nature-vs-nurture, and I really appreciate that Eowyn didn't try to answer any of the age-old questions she uses as a starting point. Eowyn also doesn't make this a fairytale. Her characters learn quite distinctly that wanting something isn't always enough.

A running joke for queer women

Alison composes a truly laugh-out-loud novel that skewers the terminally online segment of our community, in a way that makes me wonder if she meant to make as many jokes as she did. (I must confess, I have not read other Alison works before, so I'm not sure of how in on the joke she is.) Alison's novel reminds me a lot of the social commentary Glynnis MacNicol makes in I'm Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself, specifically about Gen-Z.

I suspect that this novel would be more impactful if I were more familiar with Alison's characters (from other reviews I've read, it seems these characters are familiar figures). And Alison's seeming focus on capitalism doesn't really shine through...there are some random elements that pop up throughout, but they don't seem to connect to the plot. Didn't keep me from enjoying it immensely, though!

"Cat Person," but vignettes

I remain awed by Claire Keegan's writing ability. Authors who can write engaging short stories are SO powerful—the talent it takes to evoke such depth of feeling with so few words?? Clearly, economy of language is not one of my god-given talents. In this collection, Claire creates three worlds: that of a Dublin commuter in the aftermath of his recent breakup; a writer seeking retreat finds her peace interrupted by a demanding stranger; a married woman seeking a weekend tryst finds herself in over her head (to put it mildly).

The overall vibe of this collection is unsettling. Much like the infamous New Yorker story "Cat Person," women and men may emerge from this collection with very different things. Content warning for the last story: "Antarctica." The plot has elements similar to that of Stephen King's Gerald's Game (IYKYK).

Vignettes about the color blue

A book is the best gift, to give and to get! For my birthday this year, my friend Erin brought me Maggie Nelson's Bluets! These colorful vignettes are odes to Maggie's favorite color—and "favorite" may be an understatement. Maggie obsessed with blue—every shade, tint, and hue. To Maggie, blue evokes divinity, ugliness, profanity, heartbreak, connection, sex, memory, ownership, joy, love....the list goes on. And her obsession makes this collection of vignettes read like your favorite aunt's junk drawer, full of treasured stories, anecdotes, and esoteric nuggets of research.

I really loved the way Maggie demonstrated her deft citational prowess throughout. She collects fragments that span entire schools of thoughts and eons of history, and still her writing is extremely grounded in the present. I took my time reading this one, putting it down and coming back to it over the span of several months, and each time I picked it back up, I could just slip right inside Maggie's writing. Her words are beautiful, exposing, abrasive, sheltering, and callous all at once. I think she achieved something masterful here, and I'm so grateful to Erin for bringing it into my life! (Erin is also the friend from whom I stole my utter joy of finding used books that have scribbling in them. Reading what a stranger who owned this book before you did thought was important enough to underline, highlight, circle, or scrawl in the margins is a special kind of magic, I think. And now my annotations live right alongside theirs!)

Note from Kate: Hi! If you buy something through a link on my page, I may earn an affiliate commission. I recommend only products I genuinely like & recommend, and my recommendation is not for sale. Thank you!